New 'Gas Dwarf' Class of Alien Planets Revealed

BOSTON — For astronomers, planets around other stars tend to come in two basic types: rocky worlds and gas giants. Now, scientists have identified a third class of exoplanets, called "gas dwarfs," that fall in between the others.

These gas-dwarf alien planets have thick atmospheres like their larger gas-giant cousins but never quite made it to the size of the planetary behemoths found in the Earth's the outer solar system, researchers said.

The team studied more than 600 planets discovered by NASA's Kepler space telescope and compared their sizes to the amount of elements other than hydrogen and helium contained in their star — a characteristic known as metallicity.

"We were particularly interested in probing the planetary regime smaller than four times the size of Earth, because it includes three-fourths of the planets found by Kepler," lead author Lars A. Buchhave, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement. He presented the findings today (June 2) here at the 224th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Boston. [7 Great Exoplanet Discoveries by NASA's Kepler]

"That's where you'll find rocky worlds, which are the only kinds that we would consider potentially habitable," Buchhave said.

'Sweet spot' in metallicity

The nearly 4,000 candidate exoplanets detected by Kepler were identified when they passed between Earth and their sun. The crossing dimmed the light from the host star, allowing astronomers to identify their presence, determine their diameter and calculate their orbits.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Determining the composition of a planet — and whether it is a gas giant or an enormous rocky world — requires knowing its mass. But mass is especially difficult to calculate with smaller worlds, such as the rocky bodies with the potential to host life.

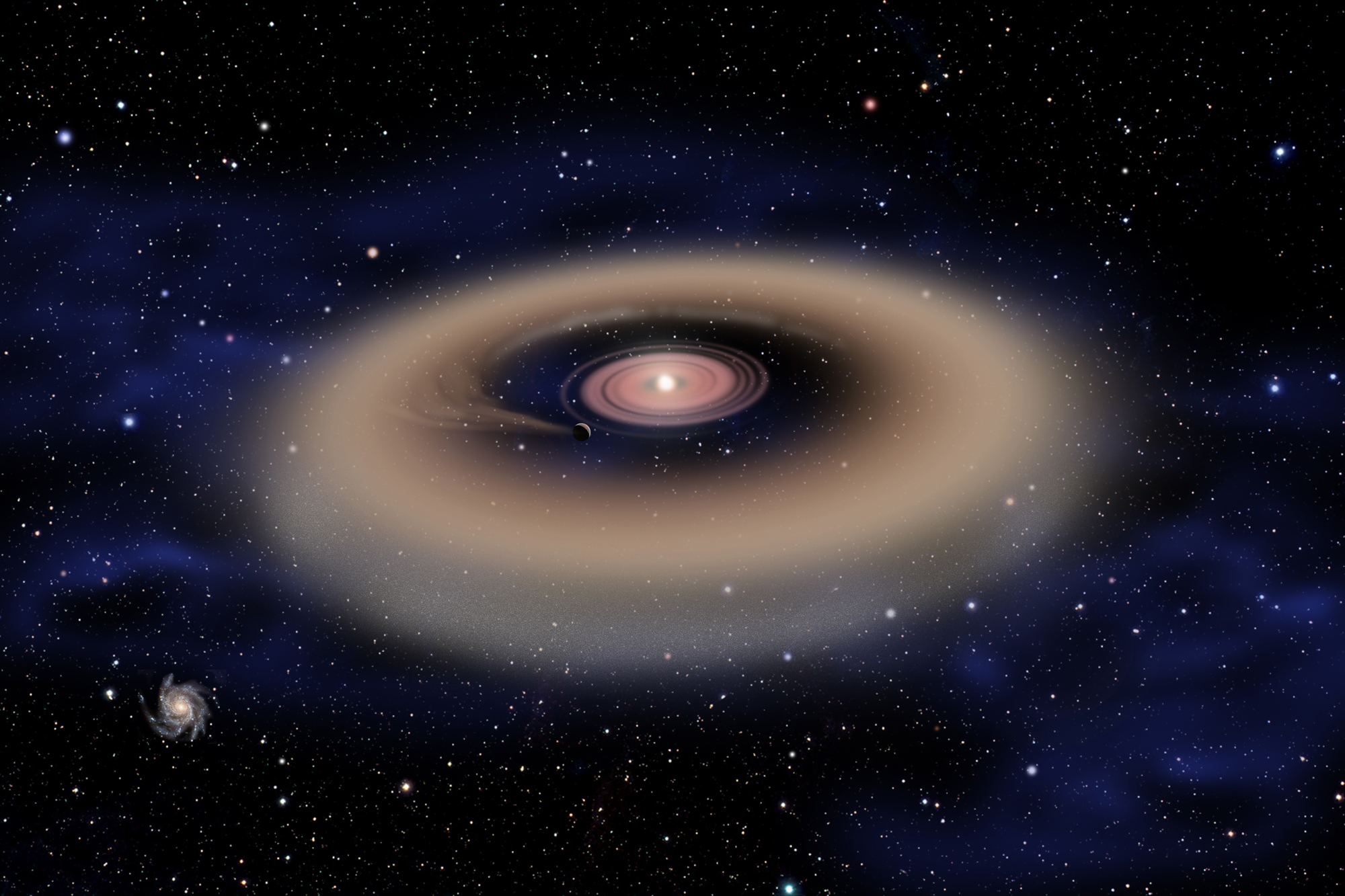

To learn more about the exoplanets orbiting a star, Buchhave and his team studied the star itself. Because planets are born from the leftover material in a disc after the formation of their sun, the makeup of the star should provide insight into the composition of the planets orbiting it, they said.

The team performed follow-up studies on more than 600 planets orbiting more than 400 Kepler stars in order to determine the metallicity of each star. Next, they performed a statistical test to determine if the newly discovered planets and the stellar metallicities corresponded.

The team found clear dividing lines at the planets that were between 1.7 and 3.9 times the size of Earth. These boundaries likely mark changes in composition as well: Planets smaller than 1.7 Earths are likely to be rocky terrestrial bodies, while those 3.9 times larger are apt to be gas giants, the researchers said.

The team dubbed the planets that lie in between the two extremes "gas dwarfs." Such planets should have thick hydrogen and helium atmospheres surrounding a rocky core, though they never reached the size of the solar system's gas giants.

Buchhave also found that rocky worlds lying far from their parent star can grow even larger than previously estimated before they accumulate their atmosphere, topping out at monstrous sizes.

Finally, the team discovered that most of the small, rocky worlds orbit Kepler stars with metallicities similar to the sun. Stars with gas dwarfs tend to be slightly more metal-rich, while those with gas giants have up to 50 percent more metals than the sun.

"It seems that there is a 'sweet spot' of metallicity to get Earth-size planets, and it's about the same as the sun," Buchhave said. "That makes sense because, at lower metallicities, you have fewer of the building blocks for planets, and at higher metallicities, you tend to make gas giants instead."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd